Canada and the Atom Bomb:

Remembering As an Act of Resistance

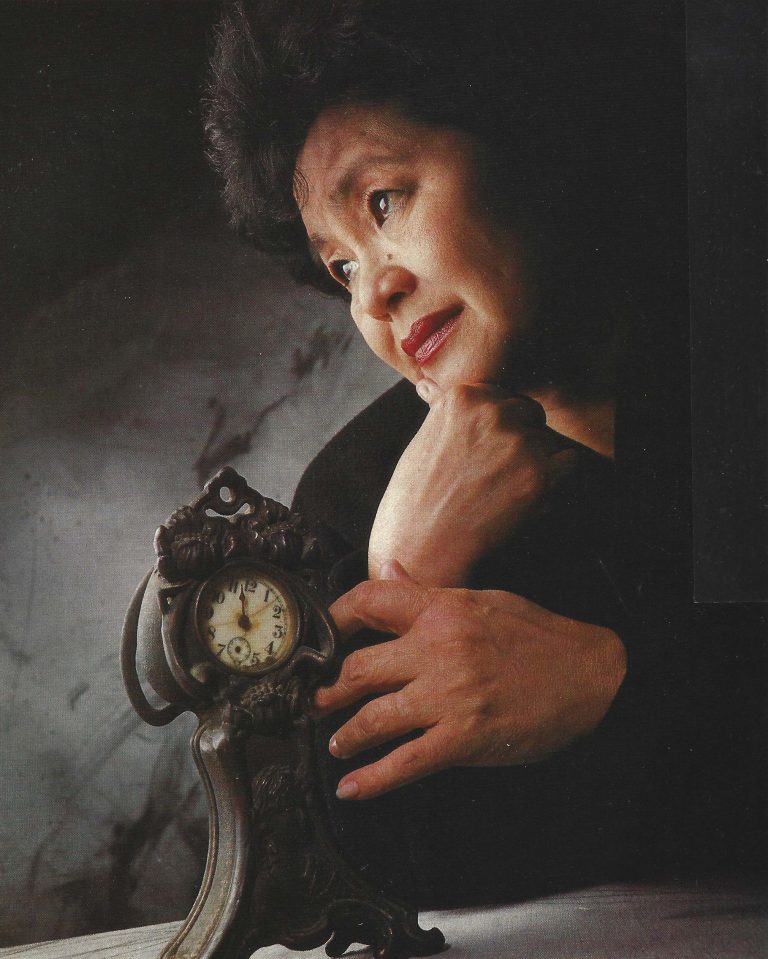

Photo by Jim Allen, Saturday Night August 1985.

I met Setsuko Thurlow in 1995 when I produced Our Hiroshima for Vision TV for the 50th commemoration of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1954, she had received death threats while studying at an American college in Virginia after criticizing the United States’ hydrogen bomb test in the Marshall Islands, one thousand times more powerful than the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima. But when she settled in Canada with her husband, Jim Thurlow, the following year, she found “a very passive, almost indifferent world here. Maybe Canadians felt they had nothing to do with the nuclear age.”

In Our Hiroshima, Setsuko singled out the Eldorado uranium refinery in Port Hope, Ontario, that enriched all the uranium used by the American Manhattan Project to produce the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. She found Canadians were not informed about their country’s involvement in the development of the atom bomb and failed to recognize that nuclear weapons were a universal, global phenomenon. “We all have to be concerned.”

The documentary showed her speaking to a huge peace rally at the University of Toronto Varsity Stadium in 1982. “Peoples around the world, with their deafening silence, have permitted their government to continue producing and accumulating ever more destructive weapons of genocide,” she told the rally. The hundreds of billions of dollars spent on armaments annually “diverted the resources that could feed the starving, heal the sick, and teach the illiterate.”

Setsuko began sharing the horrors she had witnessed as a survivor of Hiroshima with Canadians in “A Silent Flash of Light,” published in Saturday Night in August 1985. She would make these same very detailed, moving personal descriptions for international media for the next four decades. Nine members of her family and over three hundred of her schoolmates and teachers perished. Her family’s house was but ashes and broken tiles. Only an ornate clock in a cast-iron frame (seen in Jim Allen’s photograph above) could be salvaged as a reminder of life before the atomic bombing. “In the Peace Park in Hiroshima, there is a cenotaph with the inscription: ‘Rest in peace; the evil will not be repeated,’” she concluded her Saturday Night memoir. “This has become the vow of the survivors. Only then will our loved ones’ grotesque deaths not have been in vain. Only then will our own survival have meaning.”

Thirty-two years later, in December 2017, Setsuko Thurlow accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, together with Beatrice Fihn, awarded to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons for bringing about the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In her acceptance speech, she asked her audience in Oslo, “Today, I want you to feel in this hall the presence of all those who perished in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I want you to feel, above and around us, a great cloud of a quarter million souls. Each person had a name. Each person was loved by someone. Let us ensure that their deaths were not in vain.”

With the approaching 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings in 2020, Thurlow wrote to all the world’s heads of state, including Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who had not yet ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In her personal appeal to the Prime Minister, she included my research document “Canada and the Atom Bomb” that provides the factual basis for this “Canada and the Atom Bomb” exhibition.

Setsuko referred to the delegation from Deline in the Northwest Territories representing Dene hunters and trappers employed by Eldorado to carry the sacks of radioactive uranium ore on their backs for transport to the Eldorado refinery in Port Hope. The delegation travelled to Hiroshima in August of 1998 and expressed their regret that uranium from their lands had been used in the development of the atom bomb. As seen in Robert Del Tredici’s photographs, Dene had themselves died of cancer because of their exposure to uranium ore, leaving Deline a village of widows. “Surely,” Thurlow wrote Trudeau, “the Canadian Government should make its own acknowledgement of Canada’s contribution to the creation of the atom bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

She stated that an awareness by Canadians of our country’s direct participation in the atomic bombings had all but disappeared from our collective consciousness. Thurlow proposed to the Prime Minister that the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings would be the appropriate moment to acknowledge Canada’s critical role in the creation of nuclear weapons, express a statement of regret for the deaths and suffering they caused in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as announce that Canada would ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The Globe and Mail headlined her August 2020 op ed about her appeal to Trudeau, “Canada must acknowledge our key role in developing the deadly atomic bomb.”

Justin Trudeau never acknowledged receipt of Setsuko’s appeal, although Liberal MP Ali Ehsassi personally delivered a copy to the Prime Minister’s Office. With Trudeau’s refusal to meet or communicate with Thurlow, she turned her lobbying efforts to Toronto City Council. She had facilitated the creation of a large Peace Garden directly in front of City Hall as a memorial to the atomic bombings and the need for peace in 1984. As shown in the exhibition, City Council hosted Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau who turned the sod, beginning construction of the Peace Garden; Pope John Paul II kindled its eternal flame, and Queen Elizabeth II dedicated it as a lasting expression of Toronto’s commitment to peace.

Setsuko was a fierce defender of the Peace Garden when the $40 million revitalization of the City Hall Square resulted in its demolition. She was a leading figure among peace activists and community peace groups who convinced City Council to rebuild the Peace Garden on the civic square. Michael Chambers’ images capture this rededication of the Peace Garden in 2016.

The following year, Toronto City Council honoured Setsuko for her peace activism and reaffirmed Toronto as a nuclear weapons-free zone. The Toronto Board of Health held public hearings that resulted in its recommendation that City Council request that the Government of Canada sign the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. City Council passed such a motion and sent the text to Justin Trudeau, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the Minister of Health.

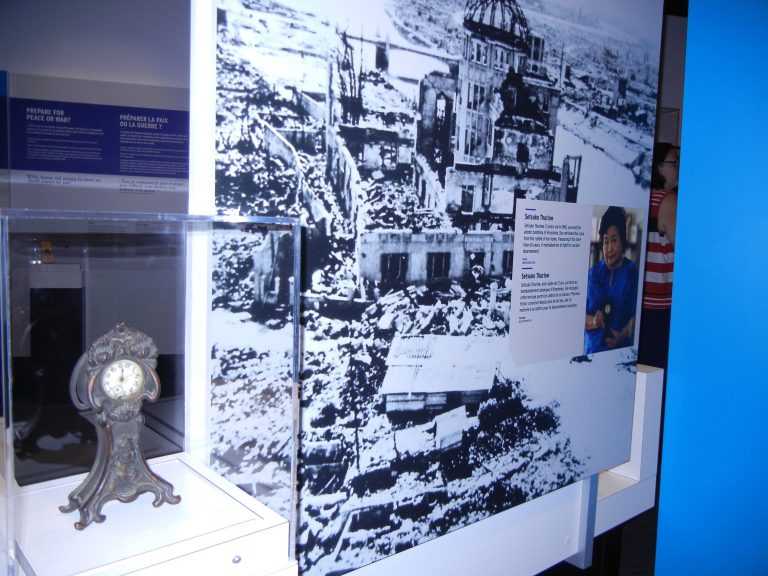

Photo of the Canadian War Museum exhibition, May 30, 2013, by Anton Wagner.

But nothing Canadian peace activists did changed the policies of the federal Canadian government. Setsuko Thurlow’s life-long commitment towards the abolition of nuclear weapons is a challenge to all concerned about the survival of human civilization. How can we transform our yearning for peace and justice into political action that will compel governments to prohibit and eliminate nuclear weapons? Setsuko donated her family’s precious ornate clock to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa for a small peace exhibit, “Peace—The Exhibition,” in 2013. Will some survivors of a nuclear holocaust digging in the rubble of what once was Ottawa find a small, charred clock that once belonged to a survivor of the first atomic bombing but whose words of remembrance of that horror were buried by the silence of political leaders?

Setsuko Thurlow addressed the 79th commemoration of the atomic bombings at Toronto City Hall in August of 2024. She recalled the courage, independence and commitment to peace shown by past Prime Ministers such as Lester Pearson, “who initiated Canada’s role as a peacekeeper during the Suez Crisis in the 1950s; Pierre Trudeau, who during a speech at the UN called for the ‘suffocation’ of the nuclear arms race; Brian Mulroney, who kept Canada out of Ronald Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’ missile defence venture; and Jean Chretien, who kept Canada out of the Iraq War.”

Setsuko deplored Justin Trudeau’s failure to support nuclear weapons abolition. “The silence from Ottawa about the nuclear weapons menace since 2015 is totally unacceptable. We are facing an ever-increasing threat of the use of nuclear weapons in the world today. Our political leaders have a moral and political responsibility to speak to us directly on a regular basis about what the government is prepared to do to ease this nuclear threat. Nothing but silence is unacceptable.”

Setsuko Thurlow at the opening of the “Canada and the Atom Bomb” exhibition, Toronto City Hall, August 2, 2024. Photo by Michael Chambers.

Anton Wagner

August 6, 2024